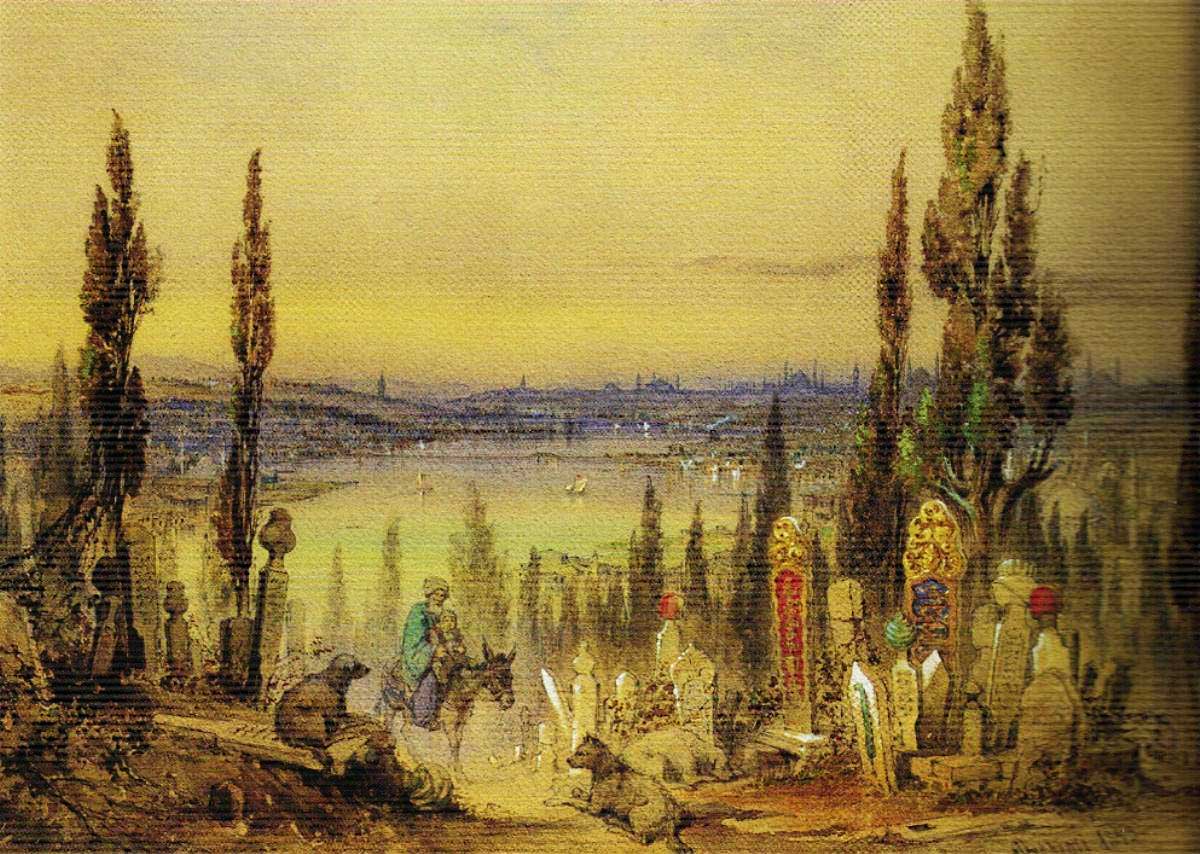

For a thousand years Constantinople was the Queen of Cities. It was the capital city of the Byzantine Empire between 330 and 1453 and the largest and richest urban centre in the world, thanks to its strategic position that dominated the trade routes. After the fall of the city to Ottoman hands, nothing really changed. The city remained its power and continued to enjoy powerful, cultural and intellectual life. In the nature of things, the city produced many great intellectuals, whose works and ideas are still discussed among the people from every corner of the world.

Here are the most famous 20 intellectuals of Istanbul who put their stamp in history with their works and ideas.

PROCOPIUS OF CAESAREA

Originating from Caesarea in Palestine (which is now Israel), Procopius came to Constantinople in his youth and became the legal adviser for Belisarius. Belisarius was the Emperor Justinian’s chief military commander, whom we know from the famous Nika Revolt in which Belisarius overpowered due to the massacre which occurred in the Hippodrome of what is known today as Sultan Ahmet Square. Procopius was alongside Belisarius in several wars fighting for the Emperor Justinian against Persia, Africa and Italy until 542. Afterwards, he wrote eight books about the wars fought by Justinian known as “Wars of Justinian”, which became the primary source of information for the rule of the Roman Emperor Justinian. Procopius also wrote “the Buildings of Justinian”, a book for Justinian’s architectural works, and “Secret History”, his most famous book, which reports the scandals that Procopius couldn’t include in his previous books. The anecdotes attack Justinian’s policies and spreads gossip about the private lives of the emperor, his wife, as well as Belisarius and his wife Antonina. Procopius’s writings situated him as a major source for the sixth century and made him become one of the greatest historians of antiquity and Byzantium.

ISIDORE OF MILETUS

Isıdore of Miletus was a lecturer in psychics at the universities of Alexandria and Constantinople and also an architect, engineer, geometer and physician. His name is usually associated with Anthemius of Tralles in the construction of the Hagia Sophia (the Church of Holy Wisdom) between 532 and 537. Neither Isidore of Miletur nor Anthemius of Tralles were educated in architecture, but they were great scientists and intellectuals that could organize thousands of labourers and loads of raw materials from every corner of the Roman Empire to build the Hagia Sophia. They are also said to be responsible for building the Church of the Holy Apostles, in Constantinople. Before he was commissioned by Emperor Justinian I to design the great church of Hagia Sophia, Isıdore of Miletus had created the first comprehensive compilation of Archimedes’ works and made a special study of domes and vaults, which helped him to build the greatest church ever.

LEO THE MATHEMATICIAN or PHILOSOPHER

Leo the Philosopher, also known as Leo the Mathematician, was said to be the cleverest man in Byzantium in the 9th century. His fame even reached the caliph al-Ma’mun, who offered him great riches to come to Baghdad. This offer of caliph al-Ma’mun showed Leo’s value to the Emperor Theophilus, who then appointed him to teach at the Church of the Forty Martyrs in Constantinople. He became archbishop of Thessalonica and later around 855, Leo was appointed to the chair of philosophy at the newly-founded school in the Magnaura Palace. As the friend of Photios I of Constantinople, who is regarded as the most influential church leader of Constantinople, Leo was a celebrated philosopher, mathematician, literary, philologist and astronomic as well as renowned for inventing a fire signal chain between Constantinople and Cilicia, which gave advance warning of Arab raids.

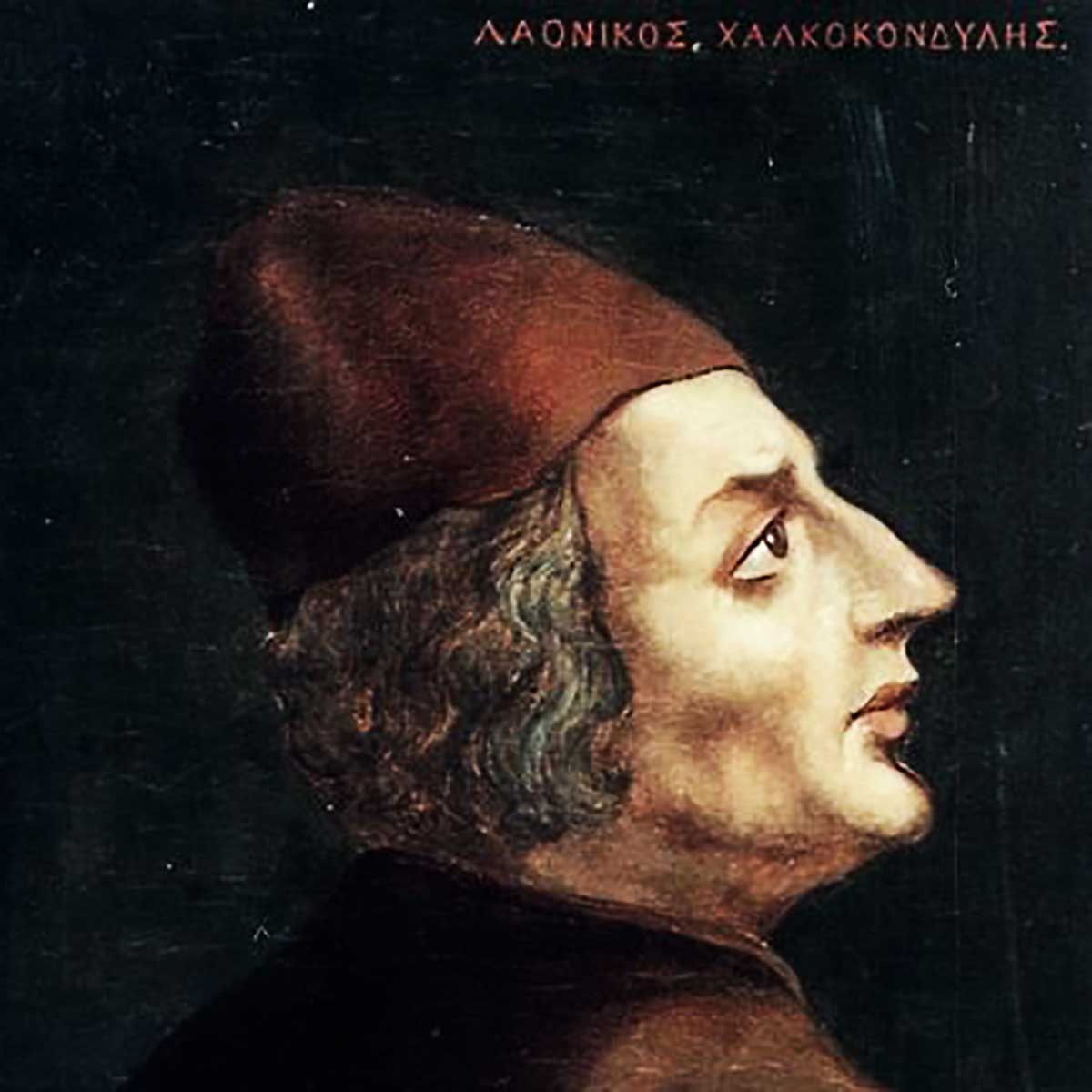

DOUKAS

The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople produced many great Greek historians such as, Chalkokondyles, Doukas, Laonikos, and Kritoboulos, to name a few. However, Doukas has a special place among all these historians during that era. It is not because he was was so handsome that girls would scream when they saw him, but because of his works; especially his accounts for the Fall of Constantinople which are regarded as the most precious sources for the last decades of the Byzantine Empire and the holy war between the Byzantines and Ottomans. If you open Doukas’s history books, you would see that his works begin with the battle of Kosovo in 1389 and continues with a detailed account of his latest mentions of the rise of Turkish arms and the capture of Lesbos by the Ottomans in 1452. Many modern historians believe that Doukas was still living in Lesbos in 1452 when it was captured by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II. It is known that Doukas survived this event, but there are no records of his subsequent life and he may have died around that time.

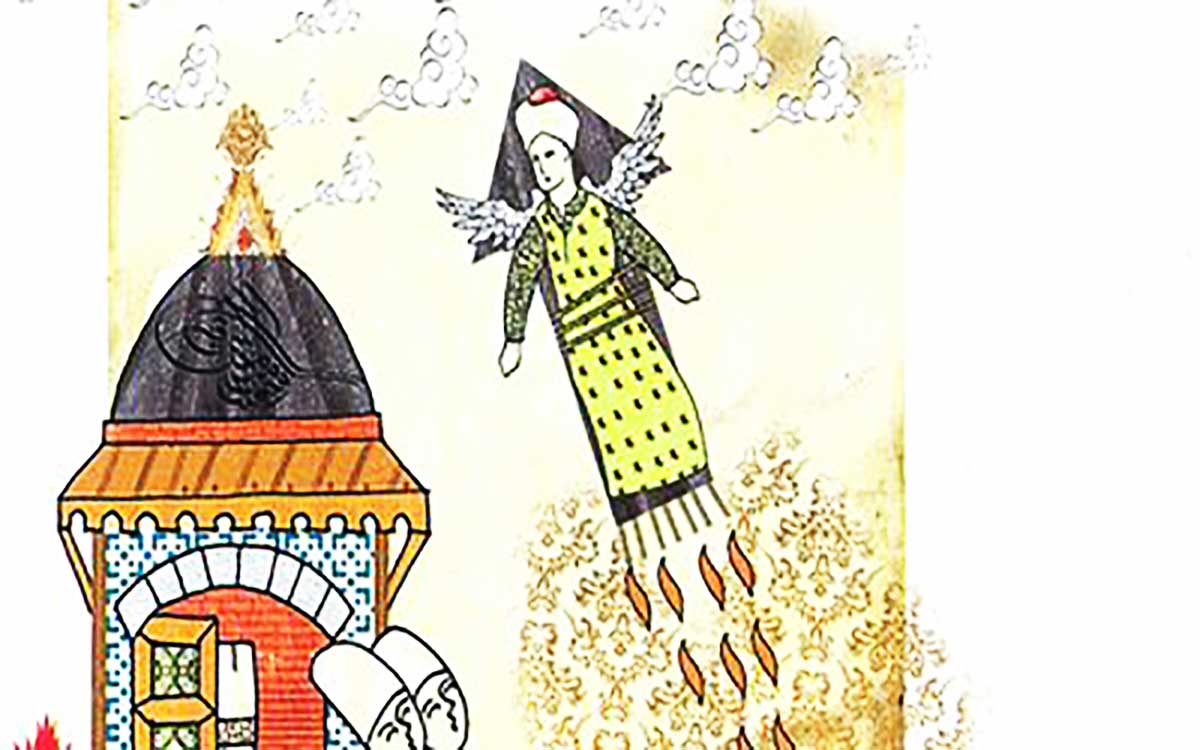

LAGARİ HASAN ÇELEBI

What is known about Lagari Hasan Çelebi, is compiled from Evliya Çelebi’s “A Book of Travels”. He recorded that Hezarfen Ahmed Çelebi flew with homemade wings across the Bosphorus from the Galata Tower to the slopes of Üsküdar. He had one of the craziest minds of his era. His brother Lagari Hasan Çelebi was no less than him. Perhaps inspired by the great success of his brother, Hezarfen Ahmed Çelebi, Lagari Hasan Çelebi designed a seven winged rocket and made a successful manned rocket flight in Istanbul. Evliya Çelebi documented that the launch occurred in celebration of the birth of Sultan Murad’s daughter Kaya Sultan. As Evliya Çelebi recorded, Lagari proclaimed before his launch “O my sultan! Be blessed, I am going to talk to Jesus.” After ascending in the rocket for 30 seconds, he opened a parachute of some kind, landed gently in the water, and swam ashore reporting “O my sultan! Jesus sends his regards to you!” Lagari was rewarded by the sultan with gold and the rank of Sipahi in the Ottoman army. His experiment is regarded as the first rocket flown in the history.

SULTAN MEHMED II

One of the most nonsensical accusations made against the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II is that he was simply a tyrannical leader with a numerical superiority in the army. Those who claim this are usually not alone in misreading Mehmed’s strength of mind and character. He had the chance to receive the best education and was supervised by the best scholars of his time. Before changing the course of human history, he developed fluency in languages including Turkish, Arabic, Greek and Slavic as well as Latin and Persian. He obtained high levels of knowledge on geography, science and politics and was also fascinated by history, philosophy and literature. He was deeply interested in the great heroes of classical antiquity. He surrounded himself with a group of Westerns, particularly Italians, with whom he discussed Alexander and Caesar, his role models for the future that he was dreaming of. All these intellectual savings can be seen in his policies which helped him to create one of the biggest empires in world history.

EBUSSUUD EFENDİ

One day, Suleiman the Magnificent was walking in the garden of the Topkapı Palace and observing the trees. He saw one of his trees was surrounded by ants. He was saddened, but couldn’t decide what to do. He asked advice from the Ebussuud Efendi. As both men were poets, Sultan Suleiman proclaimed; “Meyve ağaçlarını sarınca karınca / Günah var mı karıncayı kırınca…” (When ants surround a tree / Is there permission to kill them…) and Ebussuud Efendi replied; ”Yarın Hakk’ın divanına varınca / Süleyman’dan hakkın alır karınca…” (When time to meet the Lord comes / Suleiman will be made to pay) – The result was the Sultan could not kill the ants in fear of God Almighty. Ebussuud Efendi was promoted to Grand Mufti – supreme judge and highest official – by Sultan Suleiman in 1545, and he worked closely with the Sultan to formulate an effective and simplified code of laws known as Kanun-I Osmani (The Ottoman Laws), that served the Ottoman Empire for the next 300 years. For this, Suleiman was given the nickname Kanuni, meaning “lawgiver”. Ebussuud Efendi, who produced many great books on medicine, literature, language, law and religion, is regarded as the one of the most influential scholars of the Ottomans.

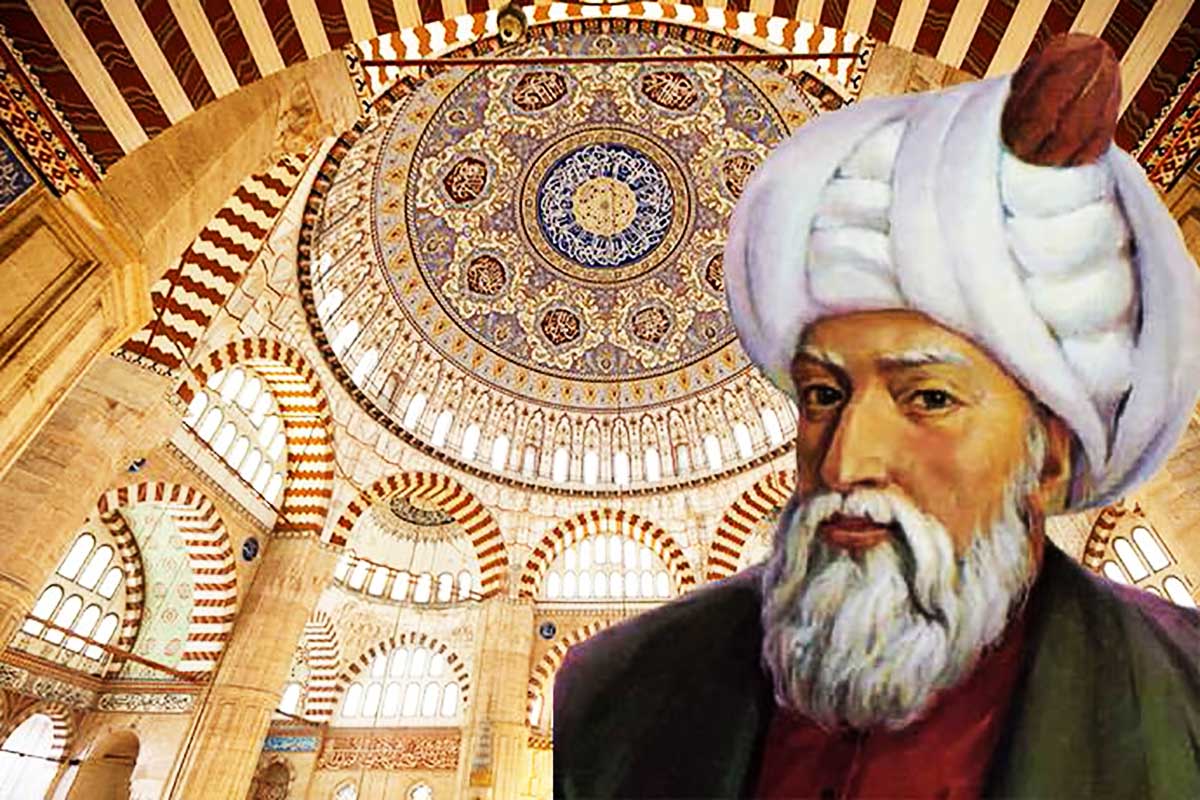

MİMAR SİNAN

The Michelangelo of the Ottomans, Mimar Sinan is known by people as the greatest Ottoman architect who shaped Ottoman architecture in the 16th century with more than 300 major structures and other more modest projects. His works can be found everywhere within the empire, in cities like Sarajevo, Mecca and Medina, but his real signature can be seen in Istanbul. He was responsible for projects like the water supply, fire regulations and the repair of public buildings. He also built many large and small mosques in Istanbul, two of which are his most famous designs. They are the Süleymaniye and Şehzade mosques, while his masterpiece is the Selimiye Mosque in the city of Edirne, almost 140 miles west. The combination of domes and minarets stretching into the sky in a majestic fashion in Istanbul is the signature of Mimar Sinan, he shaped Istanbul’s silhouette with his buildings and their effects on social life are still visible today.

KATİP ÇELEBİ

Mustafa Bin Abdullah was the most important Ottoman intellectual of the 17th century. He was born in Constantinople in 1609. Because he worked as a Janissary scribe, he was known as Katip Çelebi among the public. He was said to be a regular man; not from a family of pashas, didn’t receive formal education, but it was not difficult for Katip Çelebi to be accepted by the upper ranks of the Istanbul intellectual elite during the era all thanks to his brilliant mind. His child-like curiosity and never-ending passion to discover the truth were key aspects to his success, but the turning point in Çelebi’s intellectual career was the meeting with Qadizade Mehmed Efendi and taking lessons with him. He gained a wealth of scientific knowledge and the philosophic tradition of Islam (Sufism), and became the author of many works in the fields of bio-bibliography, geography, history, philosophy and economics. Two of his books made him a bright star of the Ottoman intellectual party during the era; “Keşfü’z-Zünun” is a bibliographic resource that is a classic on classics and his mysterious book “Cihannüma” is the most complex work of Celebi in a world of geography. According to information in one of the Cihannüma autographs, Katip Çelebi died of a heart attack on 6 October 1657. Sadly, many of his major works remained unfinished.

KOÇİ BEY

The 17th century was the best age ever to be in Istanbul. Although it was the renaissance age in Europe this moment in history was a powerful period for the Ottoman Empire as it was under the rule of the tyrannical leader, Sultan Murad IV. During this period many things occurred such as, Hezarfen flying from the Galata Tower and landing on the slopes of Üsküdar on the Asian side of Istanbul while his brother launched his rocket off the docks near the Topkapı Palace with himself inside and flew over the Bosphorus. Also, as mentioned before, two other intellectuals Katip Çelebi and Evliya Çelebi were living during this period. However, there is one more name that deserves to be on the list from this period. He is known as the Turkish Machievelli, Koçi Bey. Koçi Bey studied in the Enderun (palace school) in Istanbul, became consultant of two sultans, Murat IV and İbrahim the Mad, and prepared a series of reports about reforms in the empire. His intellectual profundity is apparent in his first report that was handed to the Sultan Murad IV. After writing for two generations following Sultan Suleiman’s death, he was convinced that his reign marked the beginning of the decadence in the empire. He saw the corruption in the “tımar” system as the main problem that was creating unrest within the empire. He suggested a smaller and more disciplined army and a more authoritarian leadership. Towards the end of İbrahim’s reign, he retired and returned to his home town Korçë for the remainder of his life. He was buried in Plamet village following his death.

MUALLİM NACİ

In the wake of the westernising Tanzimat reforms of 1839, a debate on literature between the old and the new literary schools suddenly became dense and this debate was spearheaded by Muallim Naci and Recaizade Mahmud Ekrem. Ekrem was the author of the first contemporary work of Turkish Literature – A Carriage Affair – while the followers of the old tradition gathered around Muallim Naci. Naci was born at Saraçhaneiçi quarter in 1849. He travelled a lot in Rumelia and Anatolia. After returning back to Istanbul, he worked in the Foreign Ministry, but eventually began his career in journalism. He is most known for his masterpiece work, Lûgat-i Naci, a dictionary of Turkish language, and he is also the author of poetry books, Ateşpare (1883), Şerare (1884) and Fürüzan (1885). Most importantly, his views on the need for an institution to simplify and to preserve the Turkish language were beyond his era.

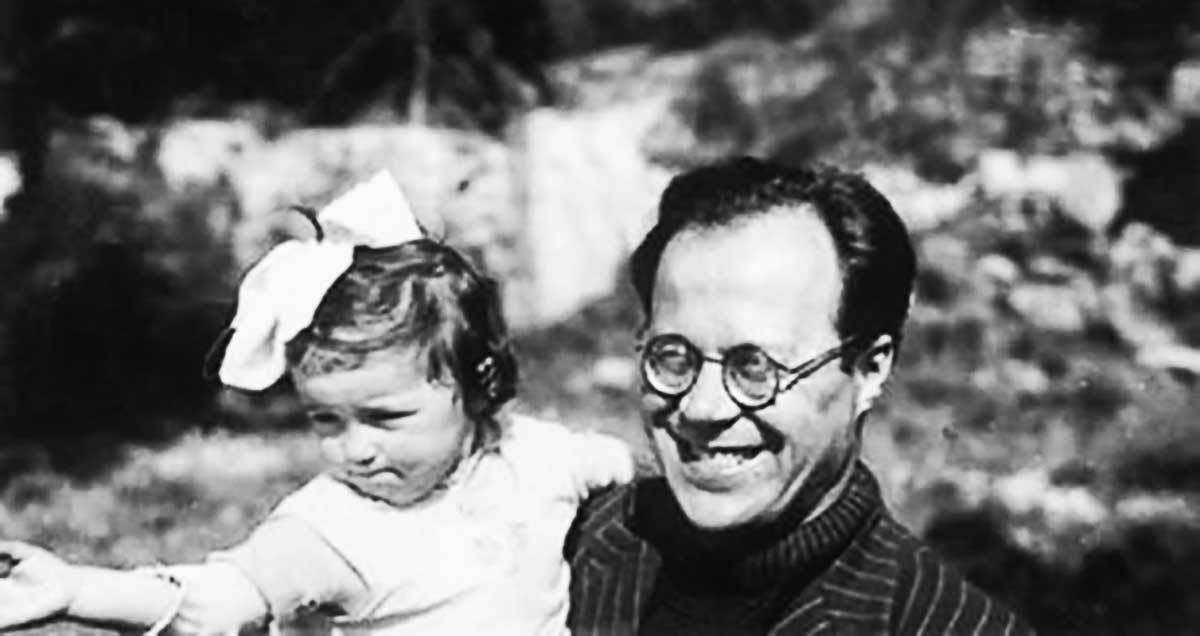

HULUSİ BEHÇET

Dr. Hulusi Behçet is one of the most famous names of Turkish medicine in the international arena. The famous German pathologist Prof. Schwartz called him a scientist who was well known everywhere except in his country, adding that you could never find him in Turkey because he was always abroad presenting his findings. Indeed, Hulusi Behçet, the first Turk who received the title of professor in Turkish academic life, described a disease of inflamed blood vessels in 1937 and this disease is universally called Behçet’s Disease in medical literature. (Morbus Behcet) He was one of the most important scientists and tutors in the field of dermatology, which he lectured at the Medicine School of Istanbul University. He was also a prolific writer and a dedicated publisher, who published important articles and reports that gained the respect of scientists from every corner of the world.

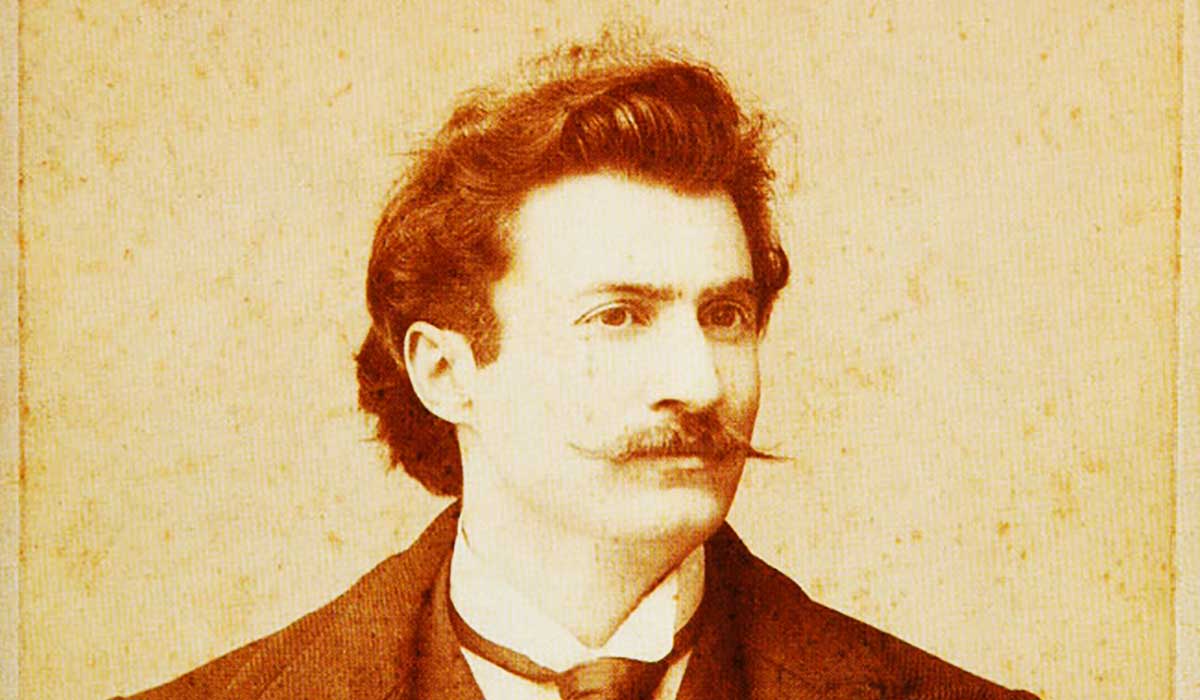

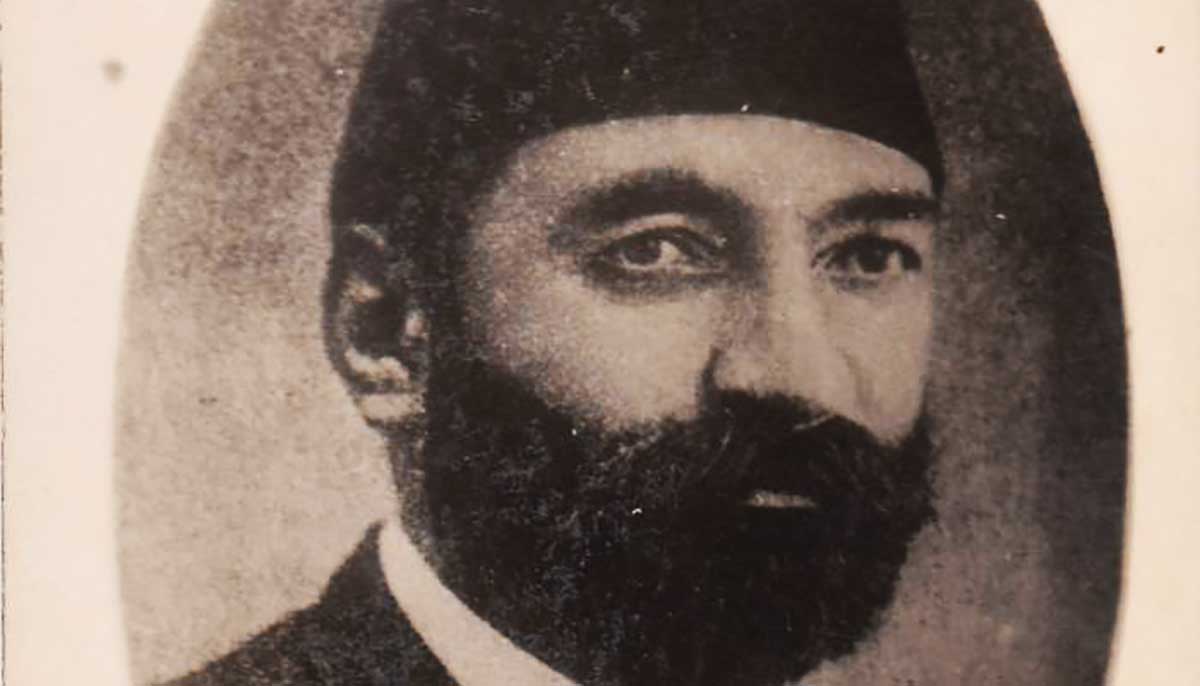

NAMIK KEMAL

The French Revolution changed peoples minds from old habits into new understandings; ‘equality, freedom, human rights, justice and nationalism’, which influenced the west and then the east and eventually everywhere. As the symbol of patriotism and freedom in Turkey, Namık Kemal, was the intellectual figurehead of the first modern political opposition known as the Young Ottoman movement, which requested an establishment of a constitutional government. This request of the Young Ottomans put them against the Sultan and his government which resulted in their fleeing from the country and seeking refuge in Western Europe. Still, Namık Kemal maintained his struggle for his ideas encouraged by his articles, novels and poems. He produced works in almost all genres of literature including novels and plays that were amongst the first of their kind in Turkish. His most influential work is the play, Vatan Yahut Silistre, which translates to “Fatherland”. ‘Vatan Yahut Silistre’ not only became a phenomenon at the time it was staged, but also had a reputation which still endures today. The founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, often remarked that he had been influenced by Namık Kemal’s writing as a young man and that they had subsequently been a source of inspiration for his goals in the formation of the Turkish government and state.

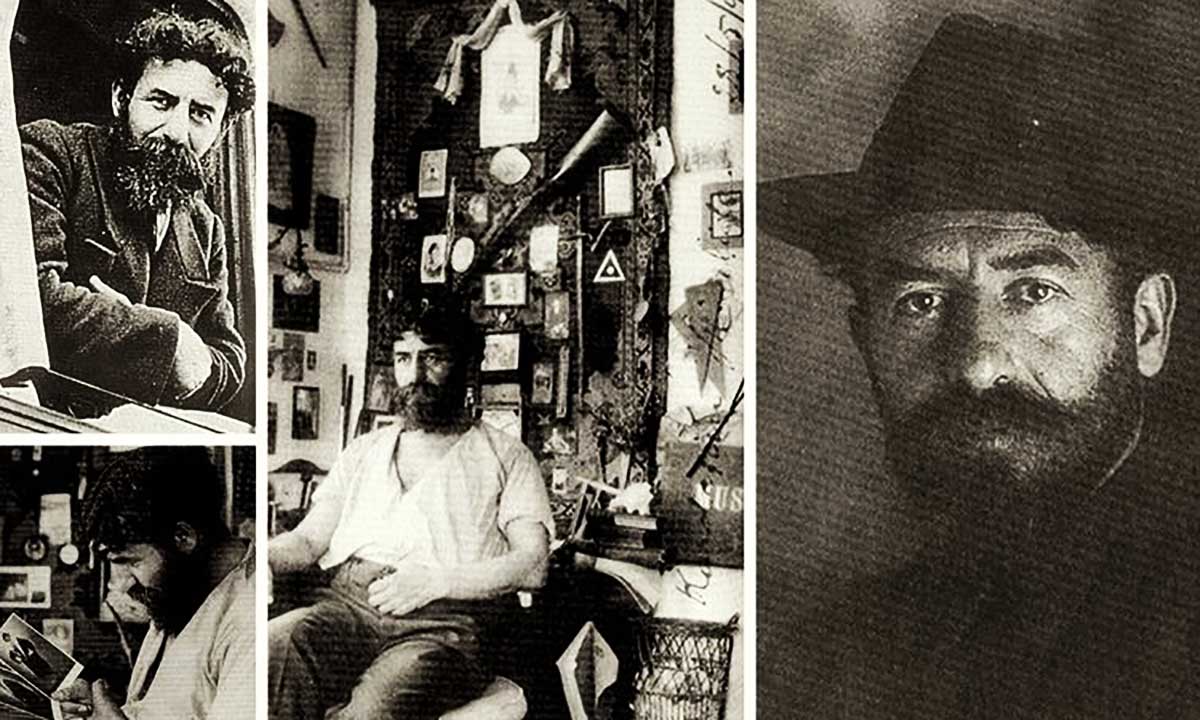

NEYZEN TEVFİK

Tevfik Kolaylı or better known by his pen name, Neyzen Tevfik, was a Turkish poet, satirist and neyzen. He was a Sufi who played ney, a reed flute that is especially popular in Mevlevi music, and that was the reason why he added the word “neyzen” (ney performer) in front of his name. Despite being a Mevlevi Sufi, Neyzen Tevfik was a very heavy drinker and was most known for his colourful bohemian lifestyle. He often introduced himself as “Neyzen Tevfik, whose three-dimensionality is manifested in his music, his poetry, and his Rakı.” His satirical poetry was critical of the conservative Sultan Abdülhamid II and it resulted in his exile to Egypt in 1903. He was forced to visit Egypt once again in 1908 and stayed there until 1913. As a poet, Neyzen Tevfik is unique in the literature of the latest Empire and early Republic. Yet, in his final years he wrote a poem called, “Türk’e Birinci Öğüt” (First counsel to the Turk), and in a section regarding religious institutions, he included this verse prior:

“Varsa aslı bunların alemde siksinler beni.”

(If any of these are true, well, fuck me.)

MEHMED FUAD KÖPRÜLÜ

“Köprülü” has always been one of the most respected family surnames in the history of the Ottoman Empire. The family provided six grand viziers with several other high-ranking officers. Mehmed Fuad Köprülü was the last honour of this prestigious Ottoman family. He was just 23 years old and without a bachelor degree, but nonetheless, his genius, limitless knowledge of history and literature convinced officials to assign him as a professor of history on Turkish literature at the Darülfünun. Köprülü was named a member of various national and foreign academies including the Soviet Academy of Sciences, the Hungarian Sandor Korosi Csoma Science Association and the Turkish Council of Historians. Several foreign universities gave him honorary doctorates including Heidelberg University in Germany, Sorbonne of Paris and the University of Athens in Greece. All the while, he was in Parliament for 22 consecutive years from 1935 to 1957. He was a member of the parliament for three successive terms during the single-party rule of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and another three terms as a representative of the Democrat Party. He held the office of foreign minister from 1950 until 1956 and played a key role in Turkey’s entering of NATO in 1952. He was a successful politician, a statesman, a sophisticated historian, a Professor of Ordinaries, was known for his contributions to Ottoman history, Turkish folklore and language. Köprülü’s major motivation in writing on history and literature was to create a modern identity for the new Turkish society and secular Muslim understanding of the Turkish state.

TURGUT CANSEVER

The philosopher architect Turgut Cansever is also known as “the wise architect”. He was not just an architect, but he was also a thinker on religious and architectural topics, and one of the first intellectuals who was vocal about architecture’s political responsibility in Turkey. He was also the only Turkish architect who received the Aga Khan awards three times. His career began with the Sadullah Pasa waterfront mansion in 1949 and continued with designing the Beyazıt Square. He worked as an adviser in the government as well, while continuing to publish articles and books. Moreover, he is the owner of the first art history doctoral thesis.

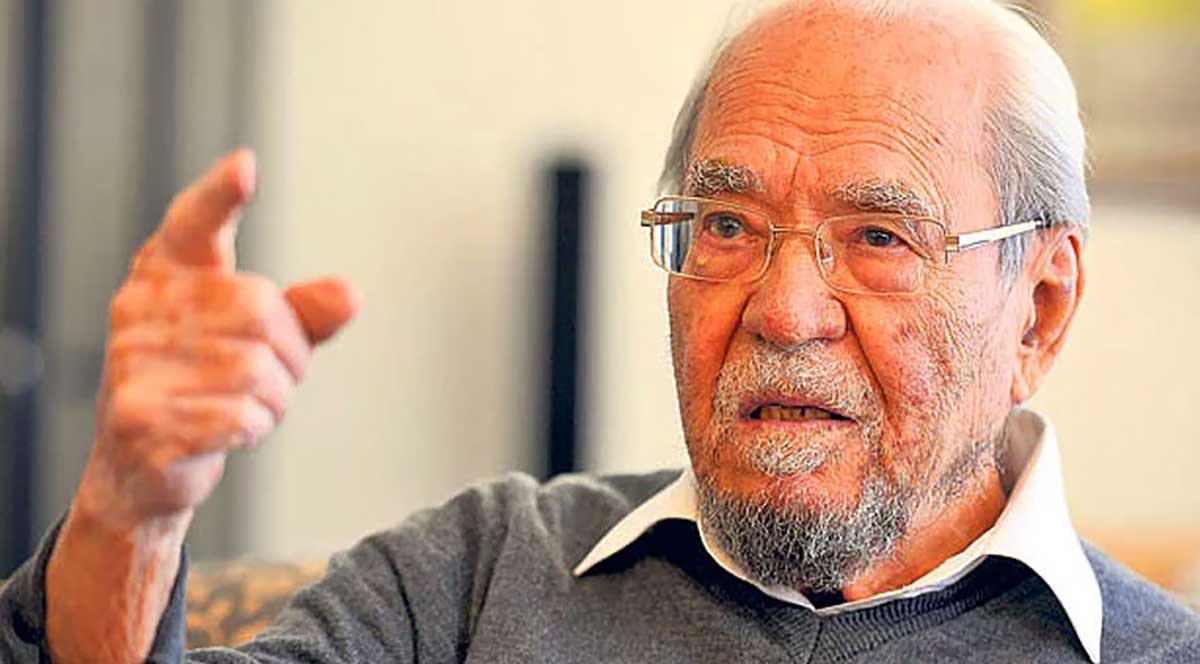

HALİL İNALCIK

Halil İnalcık is a world-renowned Turkish historian who was listed by the Cambridge International Biographical Centre as one the 2,000 social scientists who made their mark in the 20th century. Halil İnalcık lectured at many universities including Princeton, Harvard and Columbia University in the USA, and also in Ankara and Bilkent Universities in Turkey. In addition, he was the founder of the Department of History at Bilkent University. Known as the sheikh of historians, Halil İnalcık was a member and president of many international organisations. He gave various seminars and conferences in Turkey and abroad, and has written on many fields of the 600-year Ottoman rule during his 100 years of life. One of his students is the renowned historian, İlber Ortaylı, whom had stated that İnalcık was a monument of Ottoman history. Another Turkish historian, Prof. Erhan Afyoncu, also stated that İnalcık was the sheikh of historians in Turkey.

ORHAN PAMUK

Born in Istanbul in 1952, Orhan Pamuk is the face of modern Turkish literature. He is Turkey’s best-known and best-selling novelist as well as one of the leading intellectuals. He was awarded with the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2006. In the same year, Time Magazine chose him as one of the 100 most influential persons of the world. In 2005, he was honoured with the Richarda Huck Prize, awarded every three years since 1978 to personalities who “think independently and act bravely”, and he was named among the world’s 100 intellectuals by Prospect Magazine. In 2014, Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence received the European Museum of the Year Award given by the European Museum Forum in Talin.

AZİZ SANCAR

Coming from a low-income family from the town of Savur in Mardin, in southeastern Turkey, Aziz Sancar graduated from Istanbul University and completed his PHD degree at the University of Texas in Dallas. He has been a professor at North Carolina School of Medicine since 1982. He worked on mapping the cellular mechanism that underline DNA repair, which happens every single minute of the day. In addition, Sancar and his colleagues discovered how the common cancer drug cisplatin and others like it damage the DNA of cancer cells. This finding has led to further research to figure out how to better target and kill cancer cells. In 2015, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Tomas Lindahl and Paul Modrich for their mechanistic studies of DNA repair. With this great success Aziz Sancar became the first Turkish scientist to win a Nobel Prize. Aziz Sancar is a great scientist with strong political opinions. His dedication of the award to Atatürk and his vow on presenting it at the museum in Atatürk’s Mausoleum is a strong statement in favour of Turkey’s secular qualities.

IOANNA KUÇURADİ

“The reason why we suffer is ignorance”, says Turkish philosopher Ioanna Kuçuradi. She is of Greek descent, but born in Istanbul. Ioanna Kuçuradi is a leading personality in the world community of contemporary thinkers. She is most known for her efforts to promote human rights and human rights education in Turkey and abroad. She was the President of the International Federation of Philosophical Societies between 1998 and 2003 and the organiser of the 21st World Congress of Philosophy. In 1994, she was elected chair of the newly established High Advisory Council for Human Rights in Turkey. Ioanna Kuçuradi is also a holder of UNESCO Chair of Philosophy of Human Rights since 1998. In the same year, she founded the Department of Philosophy at Hacettepe University in Ankara, where she taught philosophy until 2005. She is currently a full-time academic of Maltepe University in Istanbul. Kuçuradi has received numerous honours including the Goethe-Medaille, UNESCO Aristotle Medaille, and UNESCO Human Rights Education Prize to name a few.